Not so long ago, erectile dysfunction (ED) was a problem that men seemed to accept as a natural, if frustrating, consequence of aging. Then in the spring of 1998, Viagra—the first oral medication to treat ED—hit the market, followed a few years later by Levitra and Cialis. Another ED drug, Stendra, was approved in 2012. The phenomenal response to these pharmaceutical solutions for ED has been dubbed a second sexual revolution, the first having occurred with the advent of birth control pills. Both types of medications fostered major changes in sexual behavior and the ways in which people think about and talk about sexuality.

What is erectile dysfunction?

Simply put, ED is trouble attaining and sustaining an erection sufficient for sexual intercourse. At least 25% of the time, the penis doesn’t get firm enough, or it gets firm but softens too soon.

Often, the problem develops gradually. One night it may take longer or require more stimulation to get an erection. Another time, an erection may not be as firm as usual, or it may end before orgasm. When such difficulties occur regularly, it’s time to talk to your doctor.

Causes of erectile dysfunction

Failing to have an erection one night after you’ve had several drinks—or even for a week or more during a time of intense emotional stress—is not ED. Nor is the inability to have another erection soon after an orgasm. Nearly every man occasionally has trouble getting an erection, and most partners understand that.

Often, the culprit behind ED is clogged arteries (atherosclerosis), which can affect not only the heart but also other parts of the body. In fact, in up to 30% of men who see their doctors about ED, the condition is the first hint that they have cardiovascular disease. Other possible causes of ED include medications and prostate surgery, as well as illnesses and accidents. Stress, relationship problems, or depression can also lead to ED.

Treatment of erectile dysfunction

Regardless of the cause of ED, this problem often can be effectively addressed. For some men, simply losing weight may help. Others may need medications. If these steps aren’t effective for you, a number of other options, including injections and vacuum devices, are available. Given the variety of options, the possibility of finding the right solution is now greater than ever before. See also the section on testosterone therapy below.

How common is erectile dysfunction?

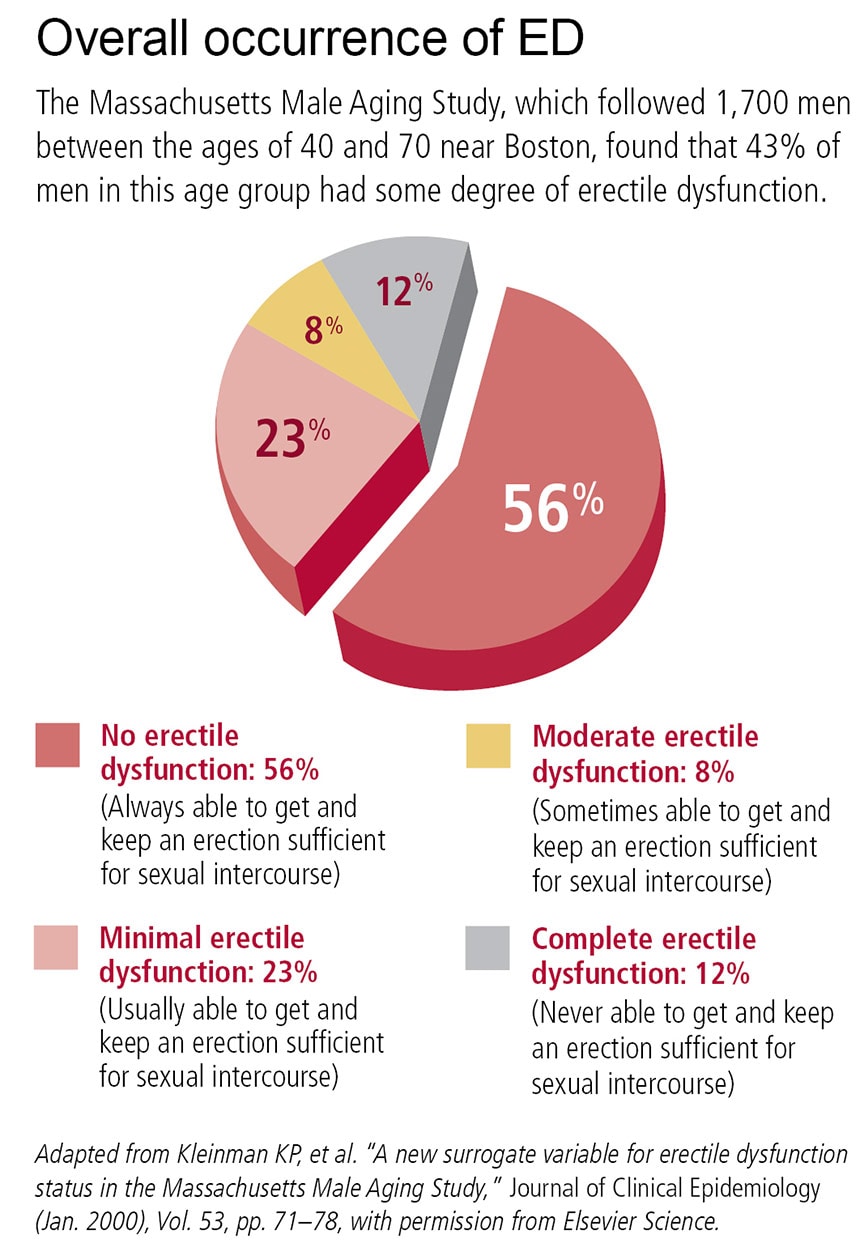

The National Institutes of Health estimates that ED affects as many as 30 million American men—and worldwide, according to estimates, the number could reach more than 300 million by 2025. However, when it comes to ED statistics and research, the gold standard continues to be a large and detailed study called the Massachusetts Male Aging Study (MMAS). Over three separate data-collection periods during a 17-year span—1987–89, 1995–97, and 2002–04—researchers collected blood samples plus health and biographical data from approximately 1,700 men ages 40 to 70 living near Boston. The MMAS researchers found that about 43% of the men had some degree of ED.

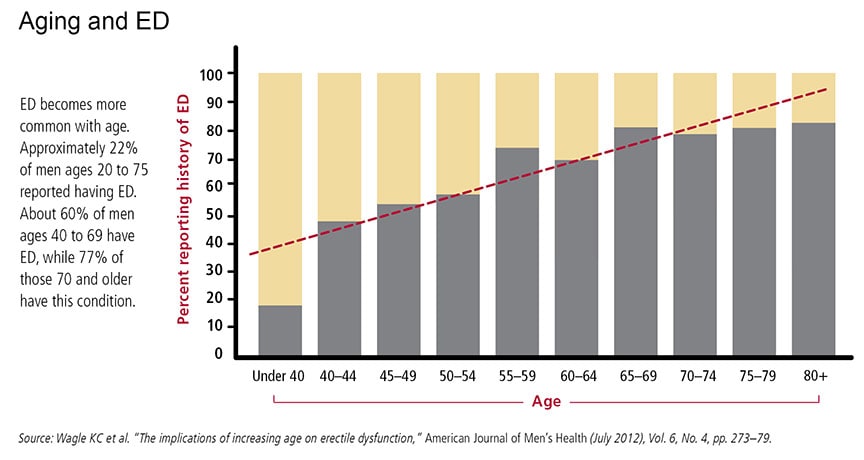

Technically, ED can strike any man old enough to have an erection, but it becomes increasingly common with age. According to the National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse, roughly 1% of men in their 40s, 17% of men in their 60s, and 48% of men 75 or older have what’s called complete ED (meaning they are never able to achieve an erection sufficient for intercourse).

Often erectile difficulties are the result of an illness that becomes more prevalent with age. Or it may reflect the treatment of such an illness—erectile difficulties are a potential side effect of many medications.

Still, this doesn’t mean that ED is something that a man simply has to live with as he gets older. It isn’t. Although testosterone, a male sex hormone that plays a role in sexual performance, tends to decline with age, it remains within normal limits in most men. And while other age-related factors can affect a man’s ability to have an erection—for example, tissues become less elastic and nerve communication slows—even these factors don’t explain many cases of ED.

Preventing erectile dysfunction

Lifestyle can have an impact on whether or not you get ED or how severe it is. Physical activity, weight loss, and good nutrition are all associated with lower rates of ED and lower severity of the problem. In part, that’s because these measures can vastly reduce your risk of atherosclerosis. They also help reduce chronic, low-grade inflammation and increase levels of the signaling molecule nitric oxide, which helps to relax blood vessels, thus improving blood flow to the penis.

If you’re a smoker, smoking cessation is another important lifestyle change. Data mined from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study found that smoking doubled the likelihood of experiencing progressive problems in having erections, and that quitting smoking can help reverse the effect. Other studies have backed up this finding.

Intriguing data from the Massachusetts study also suggest that there may be a natural ebb and flow to ED—that is, for some men, trouble with erections may last for a significant amount of time, and then partly or fully disappear without treatment. Whether this is true, and which men need treatment versus tincture of time, may be resolved through further long-term studies in other populations.

Either way, it’s clear that good sexual function is possible well into old age. Research bears out that the majority of healthy older couples can—and do—have an active sex life. In surveys, 50% to 80% of healthy couples over age 70 say they have sex regularly; half say they have intercourse once a week. And some men continue to have erections into their 80s and 90s.

How an erection occurs

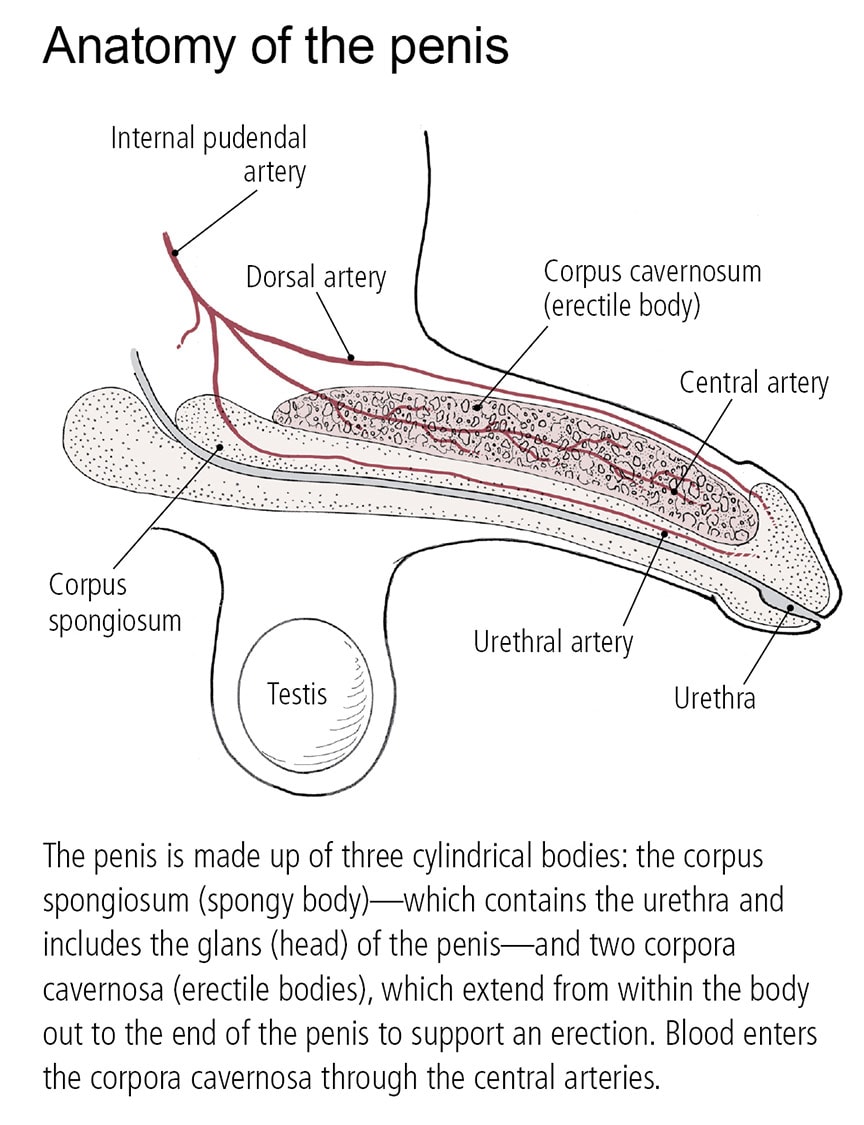

Basically, an erection illustrates simple hydraulics. Blood fills chambers in the penis, causing it to swell and become firm. But getting to that stage requires extraordinary orchestration of body mechanisms. Blood vessels, nerves, hormones, and, of course, the psyche must work together. A hitch in any one of these elements can diminish the quality of an erection or prevent it from happening altogether.

Frequently, an erection starts in a man’s brain. A sight, a touch, a smell, or perhaps just a memory sparks intense activity in the hypothalamus, an area near the base of the brain. Electrical signals of sexual arousal travel from the brain down to the lower part of the spinal cord. Nerves in this area signal nerves in the pelvis, which tell arteries to let blood into the penis and cause an erection.

Directly stimulating the genitals can also prompt an erection, though different nerve pathways are involved. Here, sexual sensation is carried by the pudendal nerve, which runs from the penis to the sacral nerves in the lower spine. The sacral nerves then send messages that cause the arteries in the penis to admit blood. During sexual activity, both of these nerve pathways are involved in producing an erection.

Nerves talk to each other by releasing nitric oxide and other chemical messengers. These messengers boost the production of other important chemicals, including cyclic guanosine monophosphate, prostaglandins, and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide. These chemicals initiate the erection by relaxing the smooth muscle cells lining the tiny arteries that lead to the corpora cavernosa, a pair of flexible cylinders that run the length of the penis.

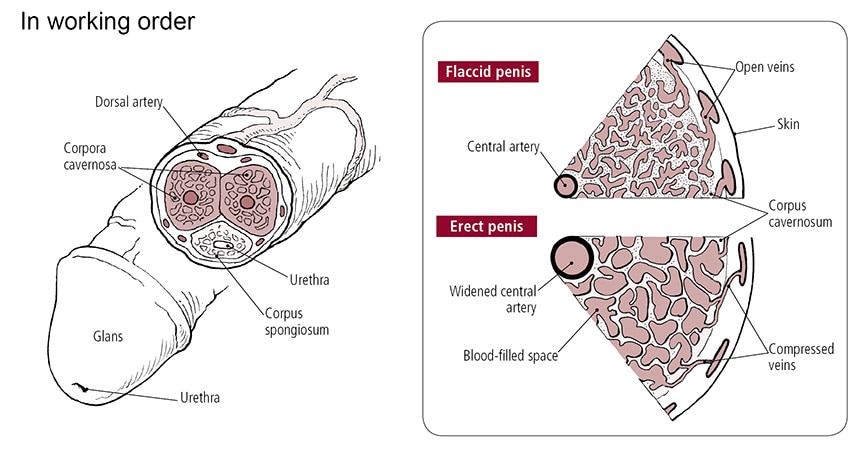

As the arteries relax, the thousands of tiny caverns, or spaces, inside these cylinders fill with blood. Blood floods the penis through two central arteries, which run through the corpora cavernosa and branch off into smaller arteries. The amount of blood in the penis increases sixfold during an erection. The blood filling the corpora cavernosa compresses and then closes off the openings to the veins that normally drain blood away from the penis. In essence, the blood becomes trapped, maintaining the erection.

Obviously, an erection isn’t permanent. Some signal—usually an orgasm, but possibly a distraction, interruption, or even cold temperature—brings an erection to an end. This process, called detumescence, occurs when the chemical messengers that started and maintained the erection stop being produced, and other chemicals, such as the enzyme phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5), destroy the remaining messengers. Blood seeps out of the passages in the corpora cavernosa. Once this happens, the veins in the penis begin to open up again and the blood drains out. The trickle becomes a gush, and the penis returns to its limp, or flaccid, state.

It’s usually difficult for a man to get another erection right away. The length of the interval between erections varies, depending on a man’s age, his health, and whether he is sexually active on a regular basis. A young, sexually active man in good health may be able to get an erection after just a few minutes, whereas a man in his 50s or older may have to wait 24 hours. One reason may be that nerve function slows with age.

Indeed, erections may work on a use-it-or-lose-it principle. Some research suggests that when the penis is flaccid for long periods of time—and therefore deprived of a lot of oxygen-rich blood—the low oxygen level causes some muscle cells to lose their flexibility and gradually change into something akin to scar tissue. This scar tissue seems to interfere with the penis’s ability to expand when it’s filled with blood.

Orgasm and ejaculation

Some men find that even though they have trouble with erections, they can still experience orgasm. That’s because erections and orgasms involve different muscles and nerves. Even if there is a breakdown along the paths to an erection, orgasm is usually still possible. By contrast, some men with normal erections can’t achieve orgasm.

The exact mechanism of orgasm is still somewhat mysterious. It’s believed to result from stimulation of the pudendal nerve. During sexual arousal, local nerves tell muscles in the testes and the prostate to contract. This propels semen forward. Nerve impulses also tighten muscles at the neck of the bladder in order to keep semen from backing up into the bladder channel and flowing out through the urethra. Doctors believe that the pressure of the semen buildup and the muscle contractions experienced during ejaculation stimulate the pudendal nerve, producing the pleasurable sensation of orgasm.

In some cases, men can have an orgasm without ejaculating. This can be a side effect of certain drugs, including the alpha blockers—such as doxazosin (Cardura) and terazosin (Hytrin)—that are used to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia and high blood pressure. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) used to treat depression and other psychiatric conditions also can induce problems with ejaculation.

Testosterone and erectile dysfunction

Because testosterone helps spark sexual interest, one might assume that low levels of the hormone are to blame for ED. It’s true that when hormone deficiency is a factor in ED, sexual desire also suffers. And according to some estimates, 10 to 20% of men with ED have hormonal abnormalities. However, the exact role that testosterone plays in ED remains unclear.

Data from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study point to an intriguing interplay among sex hormones Luteinizing hormone, made in the pituitary gland, controls testosterone levels in the body by prompting its production in the testes. Most of the testosterone in a man’s body is bound to sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG). A much smaller amount of free, or bioavailable, testosterone circulates in the bloodstream to reach cells throughout the body. Total testosterone consists of both the free and bound forms. An analysis of data drawn from 625 men showed ED was not associated with below-normal levels of total testosterone, free testosterone, or SHBG. However, men with above-normal levels of luteinizing hormone did have a lower risk for ED.

Should you worry about low testosterone?

If testosterone is the engine of sex drive, what will a blood test for this hormone tell you? Not as much as you might think. Partly, this is because large epidemiological studies are only beginning to capture data describing the normal ranges for testosterone at different ages. But more importantly, low testosterone levels can affect men differently as far as erections are concerned.

Normally, testosterone levels are highest in the morning and then vary throughout the day. A blood test can measure free testosterone—how much is circulating in the bloodstream—and testosterone bound to sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG). Total testosterone is the sum of both. Free testosterone fluctuates considerably; total testosterone is more stable. For this reason, most clinicians make treatment decisions based on total testosterone tests, using blood drawn before 9 a.m.

As a man ages, testosterone levels decline. By itself, however, a low reading—below 300 nanograms per deciliter (ng/dL) of total testosterone or 5 ng/dL of free testosterone—means little. After reviewing data on 1,475 men ages 30 to 79 who had enrolled in the Boston Area Community Health Survey, researchers reported that nearly 24% had low total testosterone, 11% had low free testosterone, and 9% were low on both markers. Yet only about 6% of these men experienced low libido, ED, lethargy, or other symptoms of low levels of male hormones (also known as androgen deficiency).

This may explain why the Endocrine Society guidelines indicate that a man should have two separate total testosterone measurements below 280 ng/dL before starting testosterone therapy. However, keep in mind that boosting testosterone levels through hormone treatments is likely to solve erectile problems only in a relatively small number of men. And since it has potential side effects, like all medications, this isn’t a treatment to undertake lightly.

Testosterone is often promoted as a “wonder drug” because of its touted potential to reignite a man’s sex drive and improve his ability to have erections. However, a reality check is in order. While testosterone therapy may help some men, it has limits and is not for everyone. There are also safety issues surrounding testosterone supplementation.

Testosterone is the hormone that gives men their manliness. Produced by the testicles, it is responsible for male characteristics like a deep voice, muscular build, and facial hair. Testosterone also fosters the production of red blood cells and increases bone density. Testosterone levels peak by early adulthood, then plateau for roughly 20 years before starting a gradual decline of as much as 2% per year around age 40. Normal levels are 300 to 1,000 nanograms per deciliter (ng/dL).

Low testosterone can cause symptoms such as ED or changes in sexual desire, depression, anxiety, and stress. However, the causal link between low testosterone and ED is not as clear as you might think. In some men with hypogonadism—a clinical condition in which the body does not produce enough testosterone—testosterone therapy does not necessarily resolve ED. Moreover, it is possible to have low testosterone levels and not experience ED symptoms.

Testosterone therapy is not easy to get. The FDA has approved it specifically for men with hypogonadism. You need to have both low levels (less than 300 ng/dL) and several symptoms to get a prescription for testosterone. A blood test measures your testosterone levels. Several tests are required, as levels can fluctuate daily and be influenced by medication and diet. In about 30% of cases where the first testosterone test is low, levels are normal when the test is repeated.

If you do receive a prescription, the hormone can be taken by either gel application or injection. With a gel, you spread the daily dose—often the size of ketchup package—over your upper arms, shoulders or thighs. Injections are given into the buttocks typically once every two weeks.

Each method has its advantages. With gels, there is less variability in levels of testosterone. (However, you have to be careful to avoid close skin contact for a few hours, especially with women, as the testosterone could cause them to develop acne or excess hair growth.)

With injections, testosterone levels can rise to high levels for a few days after the injection and then slowly come down. This can cause a roller-coaster effect, where mood and energy levels spike before trailing off. Most men feel improvement in symptoms within four to six weeks.

Can testosterone therapy help with sexual function? In one large, double-blind study of men ages 65 and older in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2016, those who took testosterone for one year saw improvements in sexual function, including activity, desire, and erectile function. Those who received a sham treatment (in this case, a placebo gel) gained no such benefits.

However, when testosterone therapy is combined with ED drugs, it appears you do not get an extra boost in sexual performance. For instance, a 2012 study in Annals of Internal Medicine examined 140 men ages 40 to 70 with ED. All took Viagra at 50 mg or 100 mg for seven weeks. Half of the group also used testosterone gel and the other half a placebo gel. The researchers found that while men’s ED scores improved with the Viagra, they did not show any additional change when testosterone was included.

Is testosterone therapy safe?

“Feeling sluggish? Testosterone therapy can help. Labs only $45.” This online pitch typifies today’s booming market in testosterone treatment. Fueled by direct-to-consumer ads on late-night TV and the Internet, rates of testosterone testing and treatment have quadrupled in the United States since 2000, according to a 2014 study in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

Despite the surge in popularity, testosterone therapy remains controversial because of its potential health risks. Safety concerns first were raised years ago when studies showed a possible association between testosterone therapy and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. However, some of these studies tested unusual circumstances. For instance, in one study, testosterone doses were much higher than what would usually be prescribed, and the subjects tended to be more frail, with other health problems.

More recent studies have shown no evidence of increased cardiovascular risk. For example, a large study reported at the 2015 American Heart Association Scientific Sessions found that healthy men with low testosterone and no history of heart disease did not have a higher risk of heart attack, stroke, or death if they took testosterone. Similarly, a 2015 study in Mayo Clinic Proceedings showed no link between testosterone therapy and blood clots in veins among 30,000 men.

Another health concern raised in previous studies was a possible link with prostate cancer. However, the relationship between the two is complex. New research has found no clear association between testosterone therapy and an increased risk of developing prostate cancer. For instance, a 2015 study in The Journal of Urology found that men who took testosterone over a five-year period did not have a higher risk. However, any man who already has known prostate cancer should not be taking testosterone, as it may drive the cancer to grow and spread.

The bottom line is that the all drugs have risks—and the long-term risks of testosterone therapy are still unknown, as many of the studies have limited follow-ups. Yet, for a selected group of men, the therapy may be a viable option, so you should discuss it with your doctor.

Talk to your doctor

If you’re a man struggling with ED, you will be glad to know that there have never been more options for treating it. The first step in most cases is simply bringing it up with your doctor—not that this is always easy to do. A study of men ages 50 and older who went to a urologist for other, unrelated problems found that 74% of those who later admitted to having ED were too embarrassed to discuss the problem with their physicians. As this report explains, though, ED is a health issue like any other—albeit a very personal one—and a frank discussion with your doctor is to your advantage.