Nearly three million Americans have glaucoma, according to the Glaucoma Research Foundation. Glaucoma is a major cause of blindness, accounting for up to 12% of all cases of blindness. The problem increases with age and begins with no noticeable symptoms. Early diagnosis and treatment can help to save vision.

What causes glaucoma?

Glaucoma damages the optic nerve. Doctors used to think that high pressure within the eye, called intraocular pressure, was the only cause, but they now know that other factors besides pressure must be involved.

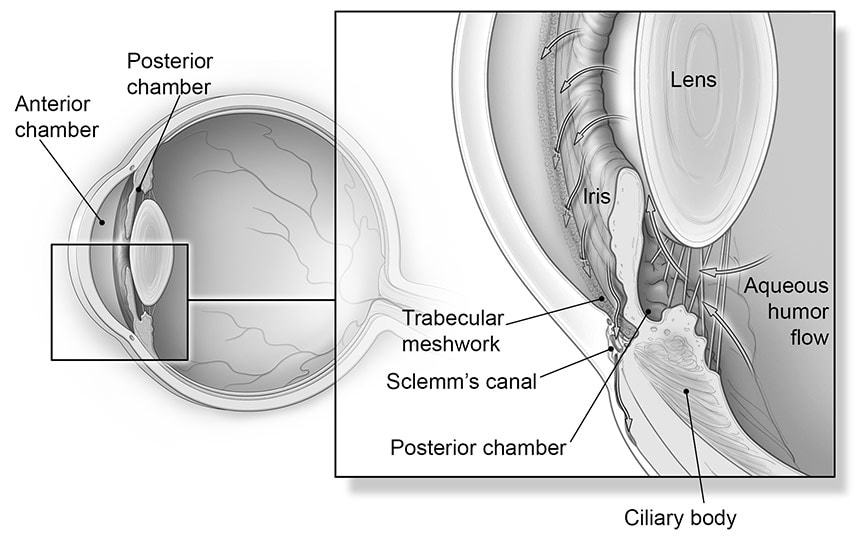

Normally, the aqueous humor—the liquid that fills the area behind the iris—circulates through the pupil into the front compartment of the eye, nourishing the lens and the cells lining the cornea. It then passes through a circular, sieve-like system of tissues called the trabecular meshwork and drains out of the eye through Schlemm’s canal into nearby tissues and blood vessels. The process keeps a healthy pressure level in the eye.

In glaucoma, this drainage system breaks down. The fluid backs up in the eye and internal pressure rises and puts stress on the optic nerve. If the pressure continues unabated, nerve fibers that carry the optical messages begin to die off and vision starts to fade. Loss of vision may also result from the obstruction of tiny blood vessels that feed the retina and optic nerve. Vision loss begins with peripheral vision and gradually closes in. The damage is irreversible.

The anatomy of glaucoma

In a healthy person, the ciliary body continuously produces aqueous humor, a clear liquid that circulates from the posterior chamber into the anterior chamber of the eye and helps maintain its shape and pressure. The fluid (see arrows above) bathes and nourishes the interior of the eye, then drains through the trabecular meshwork into small blood vessels.

If this sieve-like meshwork is blocked, aqueous humor accumulates, and pressure inside the eye increases, causing closed-angle glaucoma. In open-angle glaucoma, the meshwork remains open, but the fluid drains too slowly. In both cases, the excess fluid places undue pressure on the optic nerve in the back of the eye (not shown in image), and nerve fibers gradually begin to die off, leading to vision loss.

Types of glaucoma

Although more than two dozen types of glaucoma exist, these types affect the greatest number of people:

Open-angle glaucoma

This is the most common form of the disease, accounting for more than 90% of all cases. The name comes from the fact that the angle through which fluid drains from the anterior chamber of the eye remains open, yet the aqueous humor drains out too slowly, leading to fluid backup and a gradual but persistent elevation in pressure. Because the condition generally has no symptoms in its early stages, regular eye exams are important, especially for anyone at increased risk.

You are at higher risk for open-angle glaucoma if you:

- are African American or Hispanic

- are over age 60

- are severely nearsighted or farsighted

- have had an eye injury or eye surgery

- have a family history of the condition

- have thin corneas

- have high intraocular pressure

- use corticosteroid medications.

The importance of corneal thickness

Researchers have discovered that the thickness of your cornea (the clear part of the eye’s protective covering) plays a role in the accuracy of your eye pressure reading. Many times, people with thin corneas (less than 540 micrometers) have artificially low intraocular pressure readings. If your actual pressure is higher than the reading indicates, you might have glaucoma without realizing it.

Fortunately, there is a quick, painless test, called a pachymetry test, to measure corneal thickness. The measurement (done routinely with pressure screenings) enables your doctor to better understand your intraocular pressure reading and develop an appropriate treatment plan.

Closed-angle glaucoma

In closed-angle glaucoma, pressure in the eye rises rapidly as the angle between the iris and cornea narrows and the iris suddenly blocks the trabecular meshwork, preventing fluid from flowing out. When this form of the disorder occurs, the eyeball quickly hardens, and the pressure causes pain and blurred vision. Also, people often see halos—colored rings around lights. This condition is a medical emergency.

Low-tension (normal-tension) glaucoma

In this less common condition, the optic nerve suffers damage typical of glaucoma, but at normal eye pressures. Symptoms don’t usually appear until late in the disease, when blind spots may occur in peripheral vision, however, more sensitive diagnostic techniques are making it possible to detect this disease earlier, before peripheral vision is lost. You can usually stabilize the condition by lowering the pressure even further with medication, surgery, or both.

You are at higher risk for low-tension glaucoma if you:

- have abnormal blood flow in the eye

- have an autoimmune disease

- have low blood pressure.

Your risk for low-tension glaucoma increases if you have a disorder that affects blood vessels, such as migraines or Raynaud’s phenomenon. Several studies suggest that obstructive sleep apnea—repeated pauses in breathing that occur while you’re asleep—can affect blood flow to the optic nerve and increase optic-nerve damage in people with glaucoma.

Secondary glaucoma

Secondary glaucoma may develop as a result of another eye problem, such as longstanding inflammation, injury, cataract, diabetes, or blood vessel blockage in the eye. Corticosteroid medications can increase intraocular pressure. People who take these medicines should have their eye doctor monitor their eye pressure.

Symptoms of glaucoma

Open-angle glaucoma

- Few or no symptoms in early stages

- Blind spots and diminishing peripheral vision in later stages

Closed-angle glaucoma

- Severe pain

- Nausea

- Colored halos around lights

- Eye redness

- Blurry vision or rapid vision loss

You are at higher risk for closed-angle glaucoma if you:

- are Asian

- are farsighted

- are female

- have a shallow anterior chamber or small eye (short axial length).

Progression of glaucoma

Except in closed-angle cases, glaucoma often has no symptoms in its early stages. Even blind spots or diminishing peripheral vision may not be noticeable until the disease is advanced. Occasionally, people realize something is awry when they repeatedly need new eyeglass prescriptions or have trouble adjusting to the dark. Because glaucoma can be prevented if the condition is discovered before the nerve is damaged regular screening beginning at age 40 important.

Diagnosing glaucoma

During your exam, the ophthalmologist evaluates pressure in the eye using tonometry. Normal pressure is 8 to 21 millimeters of mercury (mm Hg), but people with eye pressure in this range may still develop the disease. Conversely, those who have slightly elevated pressure might never develop glaucoma. The amount of stress the optic nerve can withstand differs for each person and each eye.

The doctor will use both a slit lamp and an ophthalmoscope to look for deterioration of your optic nerve. If the front surface of the nerve (the optic disc) is affected by glaucoma, the doctor may see a characteristic called cupping: the disc may appear indented, and its color—normally pinkish yellow—may turn pale and more yellow because the advancing disease has hindered blood flow to the area.

If your eye pressure is not in the normal range or your optic nerve looks unusual, the doctor will perform one or two specialized glaucoma tests:

Visual field test. Also called perimetry, this test requires you to look straight ahead and indicate whether you see lights flashing on and off in different locations within your peripheral (side) vision.

Gonioscopy. This procedure involves placing a special contact lens on the surface of an anesthetized eye. The lens has mirrors and facets that, when studied through the slit lamp, give a detailed view of the corner of the eye and show whether the drainage angle is open, narrowed, or closed.

If you have glaucoma, your ophthalmologist may use fundus photography to produce three-dimensional pictures of the optic disc to serve as a baseline for the disease. If the disc changes over time, your pressure hasn’t been well controlled, and you need more aggressive treatment. Several newer techniques create computer-generated images that analyze fiber layers of the optic nerve. Over time, they can detect the loss of optic nerve fibers, allowing the doctor to track the progression of the disease.

Home testing for glaucoma

Regular glaucoma checks from your ophthalmologist are best. But having the ability to test your eye pressure at home could help your doctor better monitor your progress and adjust your medications, if needed. One option to test you eye pressure at home is iCare Home. If you choose to use a home device, first check with your ophthalmologist.

Treating glaucoma

No treatment can restore vision lost, but it is possible to stop the progression. Studies have shown that lowering eye pressure prevents optic nerve damage and vision loss in people at all stages of glaucoma.

Medications

For open-angle glaucoma, treatment usually begins with topical medications (see Table Glaucoma medications). Multiple drops and sometimes pills may be required.

| Table: Glaucoma medications These drugs are taken topically as eye drops, unless otherwise noted. Drugs listed in order the ophthalmologist is most likely to prescribe. | |

| GENERIC NAME (BRAND NAME) | SIDE EFFECTS/COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Adrenergics | |

| dipivefrin* (AKPro, Propine) | Headache, stinging, redness, burning, temporary blurring of vision. May cause pounding heart and fast heartbeat in some people. |

| Alpha agonists | |

| apraclonidine* (Iopidine) brimonidine* (Alphagan) | Stinging, burning, redness of the eyes, dry mouth, blurred vision,fatigue. Minimal effect on the lungs and cardiovascular system. |

| Beta blockers | |

| betaxolol* (Betoptic, others) carteolol* (Cartrol, Ocupress) levobetaxolol (Betaxon) levobunolol* (AKBeta, Betagan) metipranolol* (OptiPranolol) timolol maleate* (Betimol, Istalol, Timoptic-XE) | Stinging, irritation, blurred vision, tearing, allergic reaction. Elderly people are especially prone to side effects. May cause breathing problems in people with asthma. Can slow heart rate in those with heart disease. May cause mental and physical lethargy. Men may experience a decrease in libido. |

| Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors | |

| Oral acetazolamide* (Diamox) methazolamide* (Neptazane) | Dizziness, diarrhea, loss of appetite, metallic taste in the mouth, numbness or tingling in hands and feet, weight loss, fatigue, excessive urination, anemia. Can lead to loss of potassium. |

| Topical brinzolamide (Azopt) dorzolamide hydrochloride* (Trusopt) | Burning, stinging, bitter taste in mouth, corneal inflammation, allergic reaction. Dorzolamide is also available in oral form; drops have fewer side effects for most people. |

| Miotics | |

| echothiophate (Phospholine Iodide) | Blurred vision, change in near or distance vision, reduced night vision, headache, eyelid twitching, tearing, sweating, diarrhea. |

| pilocarpine* (Betoptic Pilo, Isoptic Carpine, Pilopine HS Gel, Ocusert Pilo, others) | Blurred vision, change in near or distance vision, reduced night vision. |

| Prostaglandins | |

| bimatoprost* (Lumigan) latanoprost* (Xalatan) tafluprost (Zioptan) travoprost (Travatan) | Burning, stinging, itching, redness, blurred vision. Used only once a day; some people report growth of lashes or change in eye color due to increase in brown pigment in the iris. |

| Combination medications | |

| brinzolamide plus brimonidine tartrate (Simbrinza) timolol plus dorzolamide hydrochloride* (Cosopt) timolol plus brimonidine (Combigan) | A more convenient option for people who need more than one type of medication |

| Another class of glaucoma medication known as hyperosmotics is used only to control sudden elevations in eye pressure. Hyperosmotics are given orally or by injection; examples include glycerin (Osmoglyn) and isosorbide (Ismotic). *These medications are available in generic versions | |

Surgery

If medication fails to control your eye pressure, your ophthalmologist may recommend either laser or incisional surgery.

Laser trabeculoplasty

This procedure uses very focused light energy from lasers to treat open-angle glaucoma. There are two versions: argon laser trabeculoplasty and selective laser trabeculoplasty. Both treatments effectively lower eye pressure more than 75% of the time.

Laser trabeculoplasty is done in an ophthalmologist’s office and takes about 10 minutes. After you receive anesthetic drops to numb your eye, the doctor puts a temporary contact lens on your eye, then focuses and applies the laser. You may see flashes of green or red light during the procedure. There is no pain, but you may experience blurred vision and sensitivity to light for a day or two later.

Laser trabeculoplasty benefits aren’t permanent. The treatment effect wanes within two to three years, so you may need additional medicines or more surgery.

Laser iridotomy

Doctors use this procedure to treat people who have closed-angle glaucoma. Using the laser, the doctor creates a tiny hole in your iris that allows fluid to drain from your eye and stabilize eye pressure.

Cyclophotocoagulation

Used for advanced or aggressive open-angle glaucoma when other treatments fail, this procedure can help control eye pressure. A laser is aimed at the ciliary body, the structure behind the iris that produces aqueous humor, to help reduce the amount of fluid entering the eye, which in turn lowers eye pressure.

Incisional glaucoma surgery

If medications or laser treatment fail to lower your eye pressure enough, you may need incisional surgery. Glaucoma filtration surgery (trabeculectomy) is a common but delicate microsurgical procedure is done in an operating room under local anesthesia. The eye surgeon makes a small flap in the sclera (the white of the eye), creating a reservoir called a filtration bleb under the conjunctiva, the thin, clear coating covering the sclera. The aqueous humor inside the eye can then drain through the flap to collect in the bleb, where it is absorbed by blood vessels and tissues. The doctor closes the flap with tiny stitches. Some of these stitches may be removed after surgery to increase fluid drainage. You will likely receive medications to help reduce scarring in your eye both during and after surgery.

If your doctor is concerned that a trabeculectomy will not be successful, he or she may recommend an aqueous shunt (a small valve with a tube) or an implanted stent in the meshwork between the iris and cornea to drain excess fluid.

Up to 20% of people need a second surgery. The filtering blebs created by this surgery may leak, become infected, or fail to form. Incisional surgery also may lead to blurred or reduced vision or the development of a cataract.

Several new surgical procedures can lower intraocular pressure by rerouting the aqueous fluid in a more natural way, through Schlemm’s canal. Your doctor will determine the best route for your condition.