Unlike glaucoma, which first affects peripheral vision, age-related macular degeneration (AMD) affects central vision. It strikes at the macula — the small central part of the retina that is responsible for sharp images at the center of your visual field. People with AMD often develop blurred or distorted vision and cannot clearly see objects directly in front of them. Eventually they may develop a blind spot in the middle of their field of vision that increases in size as the disease progresses.

Up to 11 million Americans have AMD, and by the year 2050 that number is expected to double to nearly 22 million. AMD is the leading cause of vision loss in adults ages 60 and older.

Types of AMD

The disease occurs in two main forms: dry and wet. While this report focuses on these two age-related forms, younger people can develop other kinds of macular degeneration, some inherited and some acquired, which may have similarities to age-related macular degeneration.

Dry AMD

The vast majority (90%) of people with AMD have the dry or atrophic type. This form of the disease is caused by a breakdown or thinning of retinal tissue and, in its advanced stages, by the loss of photoreceptor (light-sensitive) cells in the macular area of the retina. The symptoms of dry AMD become more pronounced as the condition progresses. Although some people have no symptoms and are completely unaware that they have the disease, others completely lose their central vision.

Dry AMD has three stages—early, intermediate, and advanced. In the early stage, central vision is usually not affected, though there may be some small abnormalities. In the intermediate phase, a blind spot and blurring may appear. After five years of living with intermediate dry AMD, you are more likely to develop advanced dry AMD, in which the blurring becomes more pronounced, making it hard to read or even recognize people. Dry AMD may affect only one eye at first. It is likely that the second eye is also affected without showing symptoms. The disease may continue to develop in the second eye, and symptoms can appear over time.

Wet AMD

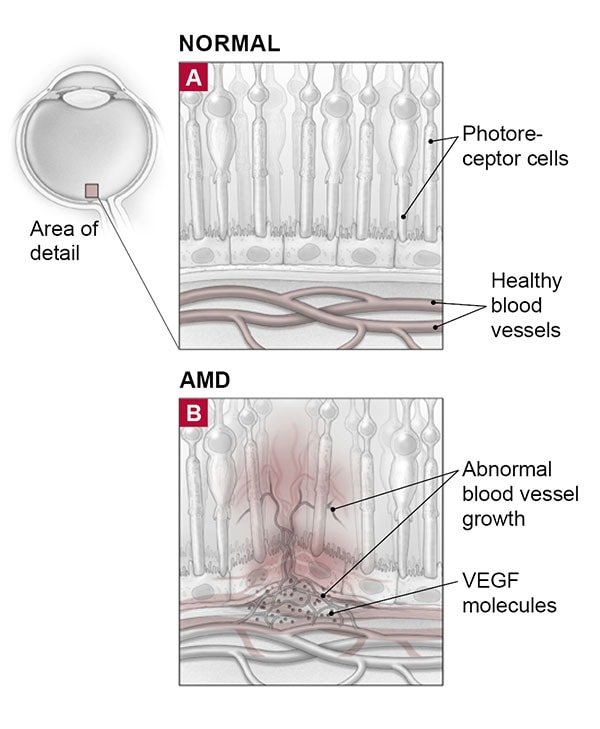

Wet AMD is the advanced, quickly progressive form of the disease that is most likely to cause severe vision loss. Everyone with wet AMD starts out with the dry form. However, only a small percentage of those with dry AMD will go on to develop the wet form. Wet AMD develops when abnormal blood vessels form in the layer of cells beneath the retina (the choroid layer) and extend like tentacles under and into the retina, often toward the macula. These new vessels are prone to leaking fluid and blood, which damage tissue and photoreceptor cells. The result is scarring and significant vision loss, usually in the center of the macula.

Causes and risk factors

The causes of AMD are not well understood. Scientists don’t know exactly why the macula deteriorates. They do know that certain factors can increase your risk of developing AMD.

- Aging. People in their 50s have only a 2% chance of developing any form of AMD. That risk jumps to 30% after age 75.

- Gender. Women get the disorder more often than men, possibly because they live longer.

- Race. White people are more likely to get AMD, and to lose their vision from it, than people of other races.

- Smoking. Smokers are up to four times more likely to develop the later stages of macular degeneration. Quitting lowers your risk, with benefits becoming evident after a year of being smoke-free.

Other factors that may increase your risk include

- coronary artery disease

- unprotected exposure to bright sunlight and ultraviolet radiation

- family history of AMD

- farsightedness

- high blood pressure

- high cholesterol

- light-colored eyes

- nighttime drop in blood pressure

- obesity

- sleep apnea

There has been some question as to whether cataract surgery may play a role in the development of AMD, particularly because many older adults have both conditions. However, research hasn’t supported this idea.

The link between diet and AMD has more evidence behind it. Studies have found that AMD is more common in people whose diets are deficient in nutrients such as vitamins C and E, the mineral zinc, and lutein and zeaxanthin (substances known as carotenoids that are found in green leafy vegetables and fruits, and which are the dominant pigments in the macula). A diet high in refined carbohydrates, saturated fat, and sugary foods such as cakes, cookies, and white bread may also raise the risk of AMD.

Ongoing research continues to focus on causes— such as genes, diet, and environmental conditions—with the hope of ultimately preventing AMD. Researchers have identified several gene variants that are linked to a higher risk for AMD, including the complement factor H gene. A few genetic tests for AMD are commercially available. However, the American Academy of Ophthalmology doesn’t currently recommend gene testing for AMD. With no real preventive therapies currently available, testing can’t do much, if anything, to change the disease course. Genetic information may be more valuable in the future, as newer and more personalized treatment options emerge.

Monitoring AMD

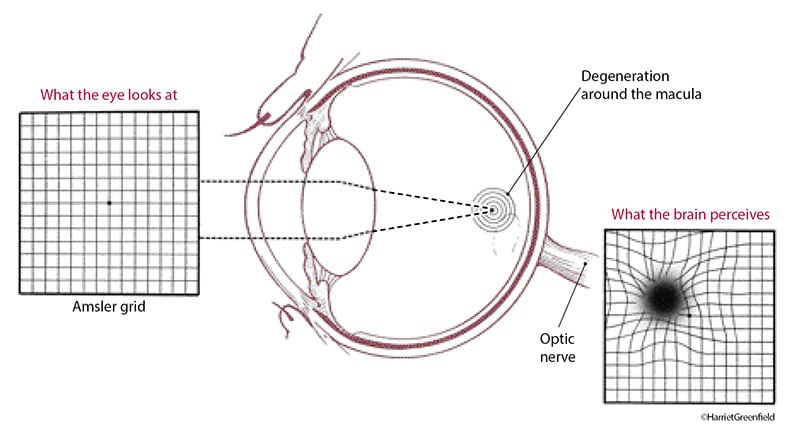

The earlier you catch the progression to wet AMD, the greater the likelihood of successful treatment. That’s why it’s important for everyone with dry AMD to get in the habit of checking their central vision at home at least once a week.

A good way to do this is with the Amsler grid test. You focus your eyes on a central dot on a grid that resembles graph paper. If the lines near the dot appear wavy or are missing, you may have AMD. (You can simulate this test by looking at windowpanes, floor tiles, or ceiling tiles to see if the straight edges look wavy.) If you already have dry AMD, it’s a good idea to perform this test regularly to check for signs of progression to the wet form of the disease. Distortion on the grid may be a sign of wet AMD and should be evaluated, especially if this distortion is new for you. You can find the Amsler grid and instructions for using it online (www.preventblindness.org/amsler-grid-instructions ), or download an app on your smartphone.

A relatively new system called ForeseeHome allows you to monitor changes in AMD at home. Looking into a mounted device with an eyepiece, you will see a succession of straight, dotted lines. When you notice a wave or bump in a line, you click on it using a mouse. It is recommended that you do this at least three to four times per week; it takes about three minutes per eye. A monitoring center assesses the results, and if it detects any changes in your vision, it alerts your doctor so that you can schedule an appointment. Medicare and many private insurance companies cover the cost.

Otherwise, you must pay a one-time activation fee and a monthly monitoring fee. In a large, government-sponsored study, people who used ForeseeHome were more likely to detect conversion to wet AMD earlier, resulting in better vision and fewer symptoms, compared with those who relied on conventional monitoring. Research shows that in general, the better your vision is when you start treatment, the better your outcome.

Treatment of AMD

Treating dry AMD

Currently, the only treatment for dry AMD is a well-balanced diet that includes leafy green vegetables— combined with supplements of vitamins studied in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS). This study found that daily high doses of vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and the minerals zinc and copper can slow (and sometimes even prevent) progression from intermediate to advanced AMD, thereby preserving vision in many people.

A follow-up study, AREDS2, sought to determine whether the formulation might be improved by adding omega-3 fatty acids, lutein, and zeaxanthin; removing beta carotene; or reducing zinc. In this subsequent study, adding lutein and zeaxanthin didn’t affect the further development (progression) of AMD, but these antioxidants were safer than beta carotene for smokers and people who recently stopped smoking, and they were particularly helpful for people who were deficient in these carotenoids. For nonsmokers, these supplements may have a modest benefit in reducing progression to advanced AMD.

Although several treatments are available for wet AMD, the dry form of the disease has been harder to conquer. In particular, researchers have focused on slowing what’s known as geographic atrophy, the most advanced stage of dry AMD, in which sections of retinal cells die and waste away. Several once-promising drugs have failed to slow the progression of this disease, and have since been shelved, but a few others are still in development. One such drug, APL-2 (pegcetacoplan), is in late-stage trials. It’s a complement C3 inhibitor, which targets the so-called complement cascade—a series of processes through which the immune system attacks the retina in AMD. In studies conducted so far, the drug slowed the rate of geographic atrophy by nearly 30% compared with a placebo (dummy pill).

Researchers are also investigating whether stem cell therapy can prevent damage to retinal cells in dry AMD. Teams at several research institutes are studying the use of stem cells to regenerate a damaged layer of cells in the back of the eye called the retinal pigment epithelium. The destruction of these cells in AMD contributes to vision loss from the disease.

Because dry AMD progresses very slowly, people are usually able to manage well in their daily routines, even with some central vision loss. If the condition worsens, special low-vision aids—such as magnifying lenses or devices that “read” regular print and then enlarge it on a monitor—can help maintain quality of life.

Treating wet AMD

Treatment for wet AMD centers on a class of medications known as anti-VEGF drugs. Laser treatment was occasionally used before anti-VEGF therapy, but it is very rarely used today.

Anti-VEGF drugs

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a substance that stimulates the growth of new blood vessels. VEGF has been linked to abnormal blood vessel growth and leakage in AMD and other common retinal diseases, such as diabetic retinopathy and retinal venous occlusive disease. Anti-VEGF drugs block the effects of VEGF, inhibiting the growth of abnormal new blood vessels.

To administer anti-VEGF treatment, the doctor first numbs your eye and then injects the drug into your eyeball with a very fine needle. Most people who receive the injection say either it doesn’t hurt or it causes mild to moderate discomfort that feels a bit like touching their eye in search of a lost contact lens. You will need injections at regular intervals for several months to several years. Possible side effects include short-term eye pain, irritation, discharge, and seeing spots or floaters, but these are often mild. More serious side effects, including infections that can lead to vision loss, occur in less than one in 2,000 to 3,000 injections.

Anti-VEGF drugs are FDA-approved for treating wet AMD. Doctors rarely prescribe the oldest one, pegaptanib (Macugen) because the newer drugs—ranibizumab (Lucentis) and aflibercept (Eylea)—are far more effective. Brolucizumab ( Beovu) was also approved for use in the treatment of wet AMD in October 2019. Another drug, bevacizumab (Avastin), is FDA-approved for treating several types of cancer, but it has long been used off-label to treat AMD.

Research suggests that Lucentis, Eylea, and Avastin are all highly effective for AMD. Avastin and Lucentis have gone head-to-head in a number of studies, and the two drugs appear to work equally well at stabilizing or improving visual acuity. For some people, one drug might work better than another.

The main difference between these drugs is the cost, which runs about $60 to $70 per dose for Avastin versus up to $2,000 per dose for Lucentis and Eylea. Check your insurance plan or Medicare coverage to see how much of the cost you will need to shoulder (if any) if you choose this therapy.

Because anti-VEGF medications act on blood vessels, some doctors have voiced concerns that these drugs might increase the risk for strokes and other vascular events. Although the long-term safety of anti-VEGF drugs hasn’t yet been fully established, so far studies haven’t found a marked increase in adverse cardiovascular events.

Despite the progress made with anti-VEGF therapies, researchers still haven’t been able to overcome one major hurdle in AMD treatment—the need for injections into the eye. A few research teams are investigating more patient-friendly drug delivery methods.

One of the simplest ways to administer these drugs would be with eye drops. Yet topical drops tested so far haven’t had much success, largely because of the difficulty in penetrating to the back of the eye. Despite the results to date, topical AMD drugs remain under investigation.

Also being studied is a sustained delivery system for Lucentis. The port delivery system (PDS) is a device pre-filled with the drug that the doctor inserts through the patient’s sclera into the vitreous cavity. The device slowly releases Lucentis into the eye over a period of several months or longer. If the PDS receives FDA approval, patients would return periodically to their doctor for a refill, but they could avoid the repeat injections currently required to treat wet AMD.

Gene therapies are also under investigation. For example, researchers are investigating whether a genetic product injected into the eye can induce a patient’s cells to produce a substance similar to anti- VEGF drugs that prevents vital cells from becoming damaged.

Laser treatments

Laser surgery is another possible—though uncommon—treatment option for wet AMD. It has lost ground to anti-VEGF drugs because it has two big drawbacks: it often fails to prevent the growth of new blood vessels, and it can destroy both diseased sections of the retina and adjacent healthy ones. Moreover, laser surgery does nothing to correct or slow the underlying disease process in wet AMD.

In general, lasers are used only in situations where the leaking blood vessels are relatively small and located far from the central portion of the macula, or when someone cannot have intraocular injections because of an eye infection or advanced glaucoma. Few people fall into these categories.

For people who don’t get good results from anti- VEGF drugs, doctors sometimes add photodynamic therapy and steroid injections. However, studies have not found that this combination treatment is any more effective than anti-VEGF drugs alone.

Preventing and slowing AMD

While there is no surefire way to prevent AMD, you can take steps to delay the disease or reduce its severity. Because smoking can accelerate AMD damage, quitting smoking is an important preventive step. Wearing a hat and sunglasses that block the sun’s blue wavelengths may also provide protection, since blue wavelengths may contribute to the development of AMD.

Evidence also suggests that certain nutrients help prevent macular degeneration. Middle-aged and older people may benefit from diets high in fresh fruits and dark-green leafy vegetables—such as spinach, collard greens, and kale—that are rich in lutein and zeaxanthin.

As for supplements, people at high risk of developing the advanced stages of wet AMD may lower their risk about 25% by taking high-dose combinations of antioxidant vitamins and minerals. However, supplements don’t seem to benefit people who either do not have AMD or who have early AMD. Ask your doctor about taking antioxidant-zinc supplements if you have intermediate or advanced dry AMD or wet AMD.

The omega-3s tested in the AREDS2 formula didn’t seem to slow AMD progression, but eating fish and other foods high in these nutrients may still be worthwhile for preserving optimal vision and overall good health.