Prostate cancer screening: What you need to know

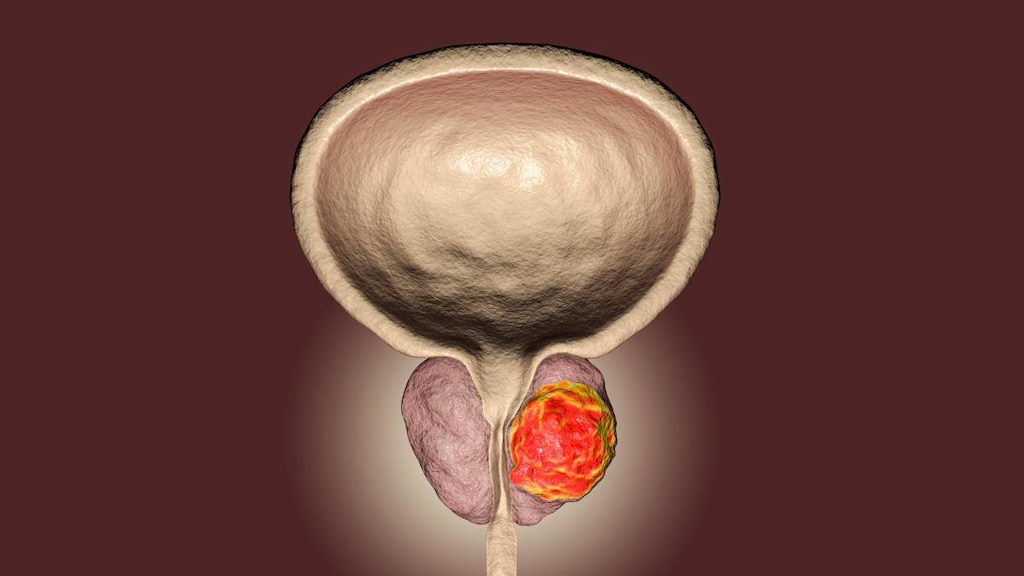

Prostate cancer is a type of cancer that can develop in the prostate, a walnut-sized gland that produces a fluid that mixes with sperm to make semen (seminal fluid). The prostate gland sits below the bladder and surrounds part of the urethra - the tube that carries urine from the bladder to the penis.

Prostate cancer is the second most common type of cancer in men in America, second only to skin cancer. It’s also the second leading cause of cancer death in men after lung cancer.

Screening tests for prostate and other cancers are used to try and detect the cancer early before symptoms develop.

What is prostate cancer screening?

Prostate cancer screening is a process of testing patients who haven’t been diagnosed with prostate cancer and who don’t have symptoms (asymptomatic) to see if they have prostate cancer. Two screening methods are commonly used to help identify men who may have prostate cancer.

Why screen for prostate cancer?

The current goal of prostate cancer screening is to help identify aggressive, localized prostate tumors in men who haven’t yet developed symptoms.

Identifying prostate cancer early in these men is hoped to:

- Reduce the chances of dying from prostate cancer

- Reduce the chances of the cancer spread to other areas of the body

- Reduce the chances of urinary obstruction, pain and other complications of advance disease

- Improve quality of life

Two tests are commonly used for prostate cancer screening

The two tests commonly used for prostate cancer screening are the:

-

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test

PSA is a protein produced by prostate gland cells, including healthy and cancerous cells. A PSA blood test measures the level of PSA in the patient’s blood.

After a blood sample is taken it is sent to a lab for analysis and the level of PSA in the sample is reported, usually in nanograms per milliliter (ng/ml) of blood.

PSA levels are commonly elevated in patients with prostate cancer, but other benign conditions such as inflammation of the prostate (prostatitis) and enlargement of the prostate (benign prostatic hyperplasia, BPH) can also cause PSA levels to become elevated.

A ‘normal’ PSA level has not been established, but PSA levels of 4.0 ng/ml or less have been considered normal in the past and levels above this lead to further investigation. Although there is still no consensus on what the PSA level cut-off should be for further investigation, higher PSA levels and PSA levels that continue to rise over time should prompt further investigation. -

Digital rectal exam (DRE)

A DRE is a test that examines the lower rectum, pelvis and lower abdomen (stomach) and it is used alongside a PSA blood test to screen for prostate cancer if required. A DRE involves your healthcare provider inserting a gloved finger into your rectum to feel the size of your prostate and also to check for bumps, hard or soft spots, and for any other abnormalities.

What happens if the initial screening tests suggest prostate cancer?

Initial screening tests need to be followed up with further testing to confirm a cancer diagnosis. The initial tests are not 100 percent accurate and could simply be picking up signs of another condition, such as a urinary tract infection or another benign (non-cancerous) condition affecting the prostate gland.

If a PSA blood test suggests prostate cancer then, depending on your results and your risk of prostate cancer, your healthcare provider may first recommend monitoring the situation for a period of time with further PSA blood tests and DREs. A urine test may also be conducted to rule out a urinary tract infection.

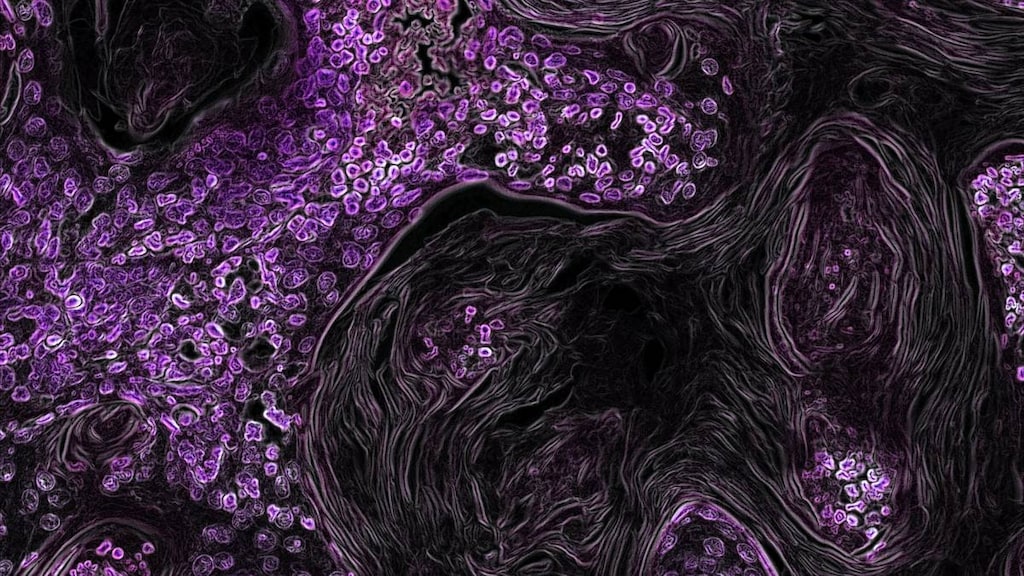

If your healthcare provider suspects prostate cancer then a prostate biopsy will be recommended. A biopsy involves using a hollow needle to get a sample of prostate tissue, which is analyzed in the lab to check the cells for signs of cancer.

Imaging tests, including an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging), a CT scan (computerized tomography scan), or a TRUS (trans-rectal ultrasound) may also be used to help confirm a cancer diagnosis and determine the stage of the cancer.

Who should be screened for prostate cancer and at what age?

Prostate cancer screening recommendations apply to men who haven’t been diagnosed with prostate cancer before and who don’t have any symptoms. The recommendations also apply to men at higher risk of prostate cancer, such as those with African ancestry, those with a family or personal history of cancer, especially those caused by high-risk germline mutations.

Different recommendations apply depending on your age. Men aged 55 to 69 years of age appear to benefit from prostate screening the most, while for other age groups the risks or harms associated with screening may outweigh the potential benefits for most men.

When deciding whether to undergo screening for prostate cancer, it’s important to discuss all the benefits and risks with your healthcare professional first to enable you to make an informed decision.

Prostate cancer screening recommendations by organization

Organization |

Age (years) |

Recommendations for PSA-based screening |

Frequency of screening |

Evidence level |

| American Urological Association (AUA) | Under 40 | Not recommended. | Grade C* | |

| American Cancer Society (ACS) | 40 | Discuss screening with patients who have more than one first-degree relative (father or brother) who developed prostate cancer at an early age (less than 65 years of age) - those at the highest risk level. |

If screening is conducted and no prostate cancer is detected then PSA results should be used to determine the time frame between screenings. PSA level 2.5 ng/ml or higher - yearly testing. |

|

| ACS | 45 | Discuss screening with high-risk patients including African American men and those with a first-degree relative diagnosed with prostate cancer at an early age. | If screening is conducted and no prostate cancer is detected then PSA results should be used to determine the time frame between screenings. | |

|

American College of Physicians (ACP) |

Less than 50 | Not recommended for average risk men. | ||

| AUA | 40-54 | Not routinely recommended. In higher risk patients, such as those with a family history of prostate cancer or of African American descent, the decision to undergo screening should be an individual one. | Grade C | |

| ACS | 50 | Discuss screening with average-risk patients who are expected to live for at least 10 years. | If screening is conducted and no prostate cancer is detected then PSA results should be used to determine the time frame between screenings. | |

| ACP | 50-69 |

Healthcare providers should inform men of the benefits and harms of screening. The decision to screen should be based on the risks of prostate cancer. Screening should not be offered to men who do not express a preference for it. |

||

| AUA | 55-59 |

Recommended depending on the patient’s situation. |

Every two years preferred (Grade C). | Grade B* |

| US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) | 55-69 |

Recommended depending on the patient’s situation. The decision to undergo periodic PSA-based screening should be an individual one. The benefits and risks of screening should be discussed to decide whether screening is appropriate. Screening may only reduce the chances of death from prostate cancer in some men. Healthcare professionals and patients should consider family history, race/ethnicity, pre-existing medical conditions, the benefits and harms of screening and treatment and the patients wishes when deciding whether or not to screen. Screening should not be offered to men who do not express a preference for it. |

Grade C | |

| USPSTF | 70 | Not recommended. | Grade D* | |

| ACP | 70 and over | Not recommended. | ||

| AUA | Over 70 |

Not recommended for men with a life expectancy of less than 10-15 years. |

Grade C |

Evidence level recommendations:

- Grade B - PSA screening is recommended because there is a high certainty that it will provide a moderate benefit or there is moderate certainty that the benefit is moderate to substantial.

- Grade C - PSA screening should only be offered selectively based on professional judgment and the patient's preferences because there is at least moderate certainty that the benefit of screening is small.

- Grade D - PSA screening is not recommended because there is moderate or high certainty that there is no benefit or the harm caused by screening is likely to outweigh the benefits.

Concerns about prostate cancer screening

Prostate cancer screening can detect prostate cancer at an earlier, more treatable stage, which seems like it could only be a good thing. However, there are concerns that for many men the risks outweigh the benefits.

- PSA tests and DREs are not 100 percent accurate. These tests may return a ‘false-positive’ or ‘false-negative’, indicating that a patient has cancer when they don’t or doesn’t have cancer when they do.

Test results that provide inaccurate information can lead to some men having unnecessary tests done and some men believing they are free of cancer when they are not. - Screening can lead to over-diagnosis and over-treatment. Some prostate cancers grow very slowly and would never trouble the patient. When these prostate cancers are picked up during screening it can lead to the patient receiving unnecessary treatment, such as surgery or radiation. This can have a significant impact on quality of life if it causes urinary or bowel issues, or affects their ability to have sex. Over-diagnosis and over-treatment may also lead to anxiety and extra costs for the patient.

- Some studies suggest that screening lowers the risk of death from prostate cancer, but the results from trials have been mixed.

It is estimated that to avoid one prostate cancer death, 1000 men aged 55-69 would need to be screened over 10 years. Approximately 100 of the 1000 men screened will have biopsy-confirmed prostate cancer.

Of the 100 men with biopsy-confirmed prostate cancer, about 20-50 percent will have cancer that never grows, spreads or causes harm, which means that they are over-diagnosed.

About 80 of those 100 men will choose surgery or radiation treatment either straight away or following a period of active surveillance. As a result of the treatment, about 50 of the 80 men will develop erectile dysfunction and 15 will develop urinary incontinence.

These outcomes need to be considered when weighing up whether to undergo screening and when deciding on the best course of action if screening results suggest prostate cancer.

Bottom line

Long-term, 13- and 18-year follow-up data from the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) and Göteborg trials shows that early detection of prostate cancer using PSA testing can lower the chances of death from prostate cancer. Despite these findings, researchers caution that the potential harms associated with screening still need to be assessed and reduced.

Other studies have not shown the same survival benefit from PSA-based screening, but the limitations of these studies is thought to have had an impact on their findings.

Prostate cancer screening is not routinely offered to all men. The decision to undergo screening should be made after weighing up all the benefits and risks with your healthcare provider.

Article references

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Prostate Cancer. January 12, 2021. Available at: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. [Accessed July 6, 2021].

- Howrey BT, Kuo YF, Lin YL, Goodwin JS. The impact of PSA screening on prostate cancer mortality and overdiagnosis of prostate cancer in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(1):56-61. doi:10.1093/gerona/gls135.

- US Preventive Services (USPSTF). Final Recommendation Statement. Prostate Cancer: Screening. May 8, 2018. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prostate-cancer-screening. [Accessed July 6, 2021].

- Carter HB, Albertsen PC, Barry MJ, et al. Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA Guideline. J Urol. 2013;190(2):419-426. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.119.

- American Cancer Society (ACS). American Cancer Society Recommendations for Prostate Cancer Early Detection. April 23, 2021. Available at: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/acs-recommendations.html. [Accessed July, 6 2021].

- Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Denberg TD, Owens DK, Shekelle P; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Screening for prostate cancer: a guidance statement from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(10):761-769. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-10-201305210-00633.

- Cancer.Net. Prostate Cancer: Screening. September 2020. Available at: https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/prostate-cancer/screening. [Accessed July 6, 2021].

- NIH, National Cancer Institute. Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Test. February 24, 2021. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/psa-fact-sheet. [Accessed July 6, 2021].

- Cancer.Net. Digital rectal exam. September 2020. Available at: https://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/diagnosing-cancer/tests-and-procedures/digital-rectal-exam-dre. [Accessed July 6, 2021].

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN Guidelines Version 1.2021 Prostate Cancer Early Detection. January 5, 2021. Available at: https://www.nccn.org/. [Accessed July 6, 2021].

- Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2014;384(9959):2027-2035. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60525-0.

- Hugosson J, Godtman RA, Carlsson SV, et al. Eighteen-year follow-up of the Göteborg Randomized Population-based Prostate Cancer Screening Trial: effect of sociodemographic variables on participation, prostate cancer incidence and mortality. Scand J Urol. 2018;52(1):27-37. doi:10.1080/21681805.2017.1411392.